The biggest, most significant practical consequence of Brexit for Ireland has not really been talked about to date. That is, that for the first time, the London government will not be in a position to continue to underwrite the Northern Ireland economy. Northern Ireland is headed for a massive economic shock.

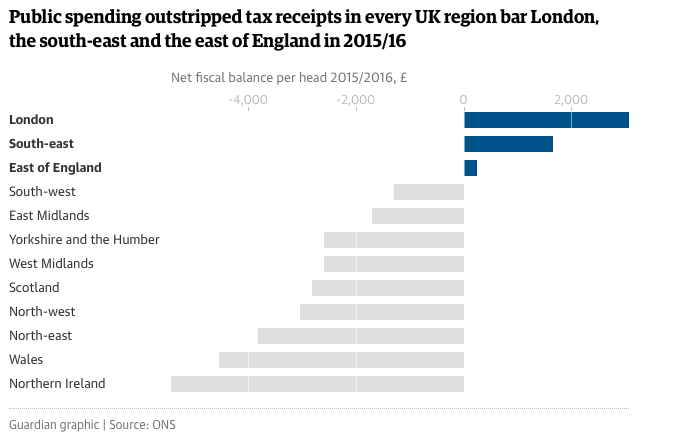

It works like this. Northern Ireland is deeply dependent on fiscal transfers (essentially payments of money) from the UK, in particular the financial service driven economies of the British south-east. There is a net transfer of £10 billion per year (£200 million per week) from the rest of the UK to Northern Ireland. NI has the highest public expenditure to person in the UK, and is highly dependent on public sector employment, much more than any other UK region. The Guardian put it in quite a stark graph:

The UK economy is in decline as a result of Brexit. Growth is slow and debt is high. How bad it gets will depend on how Brexit hits. Some say there is a full-on recession coming.

This will hit tax revenues in the UK. Getting more particular, the IMF is talking about a major reduction in sales of financial services from the UK to the European Union. Financial services alone is said to account for 11 percent of UK government tax receipts. The loss of revenues to the City will be in the tens of billions of euros. And financial services is clearly not the only sector that will be effected. Jaguar is moving operations from the UK to Slovakia, for example.

Even a few percentage points reduction in the UK tax take will have massive knock-on consequences for Northern Ireland.

London and Great Britain are going to face big economic and social problems of their own. Even the Brexit optimists agree there will be a period of upheaval. Britain is already in a major austerity program. It can’t take much more without severe political and social consequences. Northern Ireland will not be a priority if there is widespread disaffection (and maybe even riots) on the mainland.

As UK tax receipts fall, it is hard to see the axe not falling on Northern Ireland expenditure. If Northern Ireland’s subsidy per person is cut back so that it was in line with where the next biggest beneficiary is today (Wales) that would be a 20 percent cut, or a £40 million a week reduction to welfare, public employment and services like education and health. That would be a massive impact, far bigger than any benefits the DUP has gotten from its supply-and-confidence arrangement with the Conservative government.

Could Northern Ireland’s fragile political, economic and social framework really bear such a shock? Could it bear it in tandem with a cut in cross-border trade? What will all these unemployed Irish passport holders do, or where will they go? The impact of Brexit on Northern Ireland (and by extension Ireland) will be far more all-pervading than changes at the border.